Wilt Chamberlain is in his apartment having sex with one of the 20,000 women he scored over the years.

The sex was good and Wilt didn’t drop her off until six o’clock the next morning. Then he rushed to Penn Station and caught the eight o’clock train to Philly.

Friends met Wilt at 30th Street Station. They ate a leisurely lunch, so leisurely Wilt almost missed the team bus. Wilt played for the Philadelphia Warriors and they were playing a home game on-location that night, some 85 miles west of Philly a the Hershey Sports Arena in Chocolate Town, USA.

Attendance at NBA games was sparse back then. Owners were scratching and clawing to attract paying customers. So that night Warriors owner Eddie Gottlieb took his show on the road, versus the New York Knicks. Hoping to fill all 8,000 seats in the Sports Arena he also scheduled a preliminary match-up. That game featured players from the Philadelphia Eagles and Baltimore Colts and Hershey was Colts country he expected to sell out the arena.

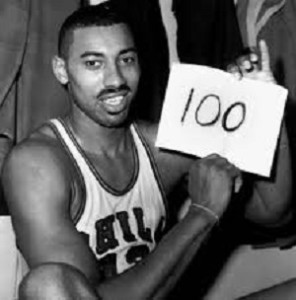

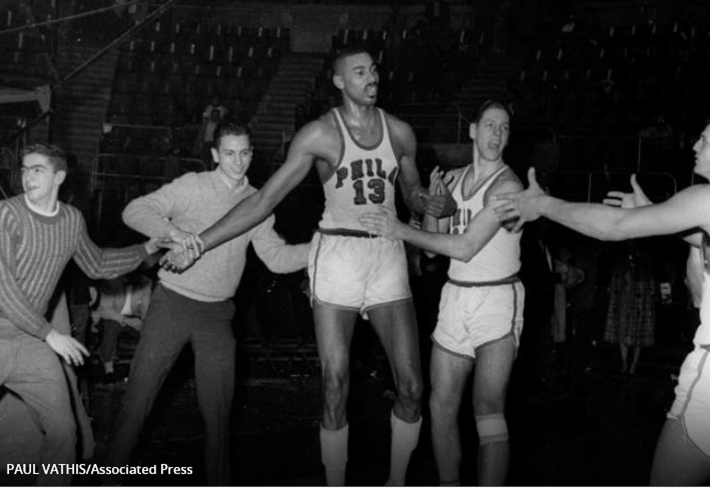

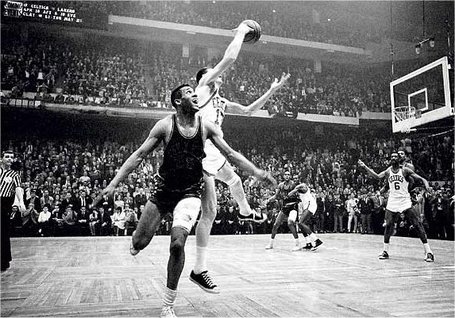

But only 4,124 spectators paid to see the doubleheader and the game would have flown under the radar except for one thing – Wilt Chamberlain scored 100 points and set an NBA record that still stands.

The game was not shown on TV that night. Bill Campbell was broadcasting the play-by-play on the radio.

I was doing my homework 62 miles south of Hershey and listening to Bill Campbell in secret through a plug in my ear connected to a transistor radio. Transistor radios were contraband at the Naval Academy Prep School (NAPS) in Bainbridge, Maryland, and that’s where I was doing my homework.

The school sat on a plateau overlooking sleepy Port Deposit, population 600-or-so. Th school was located on the east bank of the Susquehanna River some 40 miles north of Baltimore. he school was a complex of impressive beaux-arts-style buildings that originally comprised the Jacob Tome boarding school for boys. But the Navy purchased the buildings and land in 1942 and made it part of the Bainbridge Naval Training Center.

We went to class inside snazzy buildings, but we lived in military-style wooden barracks built during World War II. We studied and slept in cubicles, four men to a cube, but it was home.

I went to NAPS to play football, and study. Prepping was a common practice back then. You gained a year of maturity, size, and strength. NAPS was going to be my gateway to the Naval Academy five months hence.

I was fortunate to play both football and basketball at NAPS and since basketball was my passion, I risked the consequences of getting caught listening to the Warriors game. While listening and studying, I also kept score in a scorebook I maintained over the years.

One of my roommates was Farlin W. Arrington, just call him Arr-Snatch, from Boise, Idaho. By the way, Far introduced me to weight-lifting. There were no weight-training facilities back then in any sports but Far knew about weight-lifting. By mail-order, he bought 100 pounds of weights, along with a barbell and two dumbbells. He then taught me the basics and I soon boasted these things called lats.

I connected with Far two years ago after an absence of 55 years. You see, I got kicked out of the program three months later, in June, two weeks prior to reporting to the Naval Academy. I still remember standing there and balling my eyes out as my classmates pulled out on buses bound for Annapolis.

No, I didn’t get kicked out for listening to the game that night.

Far Arrington graduated from the Academy in 1966 as an officer and a gentlemen. And he flew A-4’s for ten years protecting you and me.

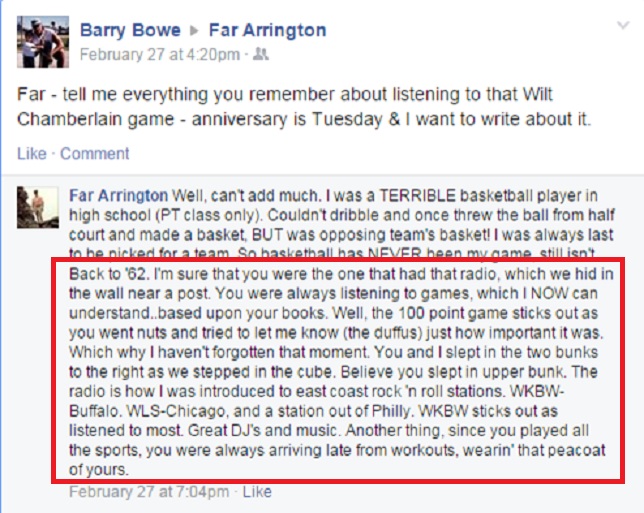

I asked Far what he remembered about that night and here’s what he said:

There you have it. I hid the radio in the wall, near a post.

Below is the box score I found on the Sixers website.

For me, that night occupies a special place in my heart. I experienced that like no one else in the world secretly listening to Bill Campbell on a transistor radio and hoping not to get caught.

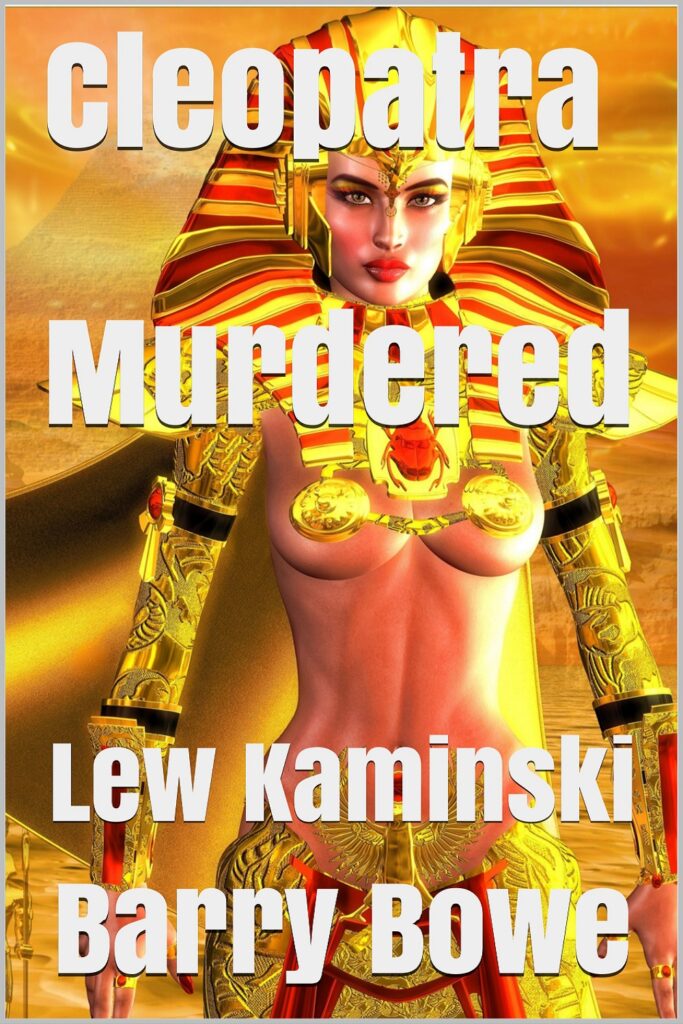

Barry Bowe is the author of Born to Be Wild.

Comments

No Comments