We played stickball every day during the summer. But in our version of stickball, we didn’t use a ball. We cut a garden hose into pieces about four inches long and called it hoseball.

We played stickball every day during the summer. But in our version of stickball, we didn’t use a ball. We cut a garden hose into pieces about four inches long and called it hoseball.

The year was 1954 and I was eleven. We played in the street and used the tar-lines to mark our singles, doubles, triples, and home runs. We started a league and Jimmy Mayrides got the first pick. He took the Phillies as his team and I took the Braves.

It worked out fine because I was exposed to players I would’ve otherwise ignored.

Prior to that 1954 season, the Braves moved from Boston to Milwaukee and they were loaded with good players. Warren Spahn, Lew Burdette, Bob Buhl, and Gene Conley made up the core of the pitching staff.

I included Gene Conley because he pitched for the Phillies in 1959 and 1960. Because he was 6-8 and played college basketball at Washington State, he also played for the Boston Celtics as a backup center in 1952-53 – and then again from 1958 thru 1960. By the way, the Celts won the NBA championship in every one of Conley’s final three seasons with the team.

The Braves also had a trio of great position players – Joe Adcock, Eddie Mathews, and a 20-year-old rookie named Hank Aaron. No way any of us could’ve imagined that Aaron would one day break Babe Ruth’s home run record and become one of the greatest players in MLB history – but he did.

What drew my attention to Hank Aaron just now – other than the fact that he celebrated his 81st birthday three days ago, on February 5 – was that I heard that he was trying to buy the NBA’s Atlanta Hawks.

Where in hell did Hank Aaron come up with enough money to buy the Hawks?

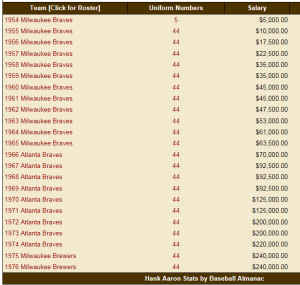

If Hank Aaron played today, his contract would call for about $-jillion. But Hank Aaron doesn’t play today. He last played nearly 40 years ago and ballplayers didn’t make millions back then. They had to get off-season jobs just to make ends meet.

For instance, during Aaron’s junior year in high school, way back in 1950, he played for the semi-pro Pritchett Athletics and he earned $2 per game. The next season he moved on to the Mobile Black Bears because he got $3 per game instead of $2.

In November of 1951, a scout from the Indianapolis Clowns, from the Negro American League, signed Hank to a contract that paid him $200 per month. And “Hammerin’ Hank” – as he would come to be called – excelled with Indianapolis – so much so that a year later two big league teams came calling – the New York Giants and the Boston Braves.

“I had the Giants’ contract in my hands,” Aaron recalls. “But the Braves offered fifty dollars more a month. That’s the only thing that kept Willie Mays and me from being teammates – fifty dollars.”

There’s a movie line from the 1980 comedy Used Cars that my son and I are always quoting – “Fifty bucks never killed anybody.”

In Hank Aaron’s case, fifty bucks changed the course of baseball history. Can you imagine Willie Mays and Hank Aaron playing in the same outfield with the Giants for twenty years or so?

But back to my point about money.

Hank Aaron didn’t crack the $100,000 barrier until his 17th years with the Braves. That contract called for $125,000 for two seasons. He then made $200,000 for two seasons, $220,000 for one season, and then he peaked out at $240,000 in his final two years in the big leagues. That’s chump-change compared to today’s ballplayers.

So I had no idea how Hank Aaron could accumulate wealth after baseball. Is there that much money in signing autographs?

As it works out, Hank Aaron doesn’t have sufficient wealth to buy an NBA franchise. He’s part of a group of potential investors.

We’ll see what happens.

Barry Bowe is the author of Born to Be Wild and 1964 – the Year the Phillies Blew the Pennant.

Comments

No Comments