It happened fifty years ago today – April 15, 1965.

It happened fifty years ago today – April 15, 1965.

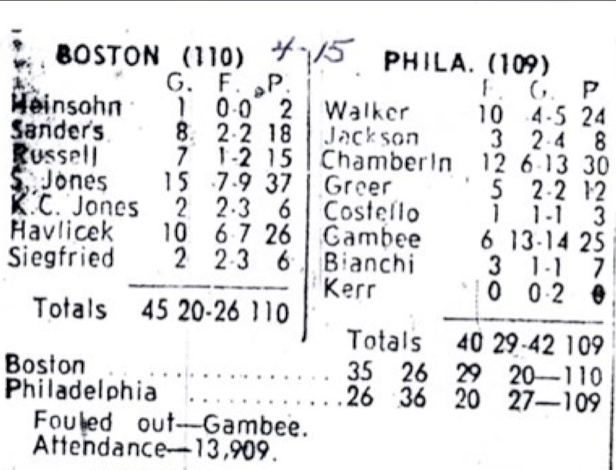

It was Game 7 of the NBA Eastern Division Finals – the Sixers versus the Celtics at the hallowed Boston Garden. The series was tied at three games a piece.

Trailing 90-82 after three quarters, the Sixers rallied furiously down the homestretch. But with five seconds left to play, it looked like the Sixers rally was going to fall just short. The Celtics were clinging to a 110-109 lead.

This was just the Sixers second season of existence since the Syracuse Nationals relocated its franchise to Philadelphia to begin the 1964 season. Prior to that, the city had been without an NBA team since the Warriors moved to San Francisco three years earlier.

The ball belonged to the Celtics under the Sixers basket.

Bill Russell was preparing to inbound. All he had to do was toss the ball into a teammate and the game was all but over. That teammate would either catch the ball and dribble off the final five seconds, or else he’d catch the ball and get fouled. He’d then march to the foul line at the far end of the court with a chance to seal the victory.

There was no three-point shot back then. So one free throw guaranteed no worse than a tie for the Celtics. Two free throws would end the Sixers season. There just wouldn’t be enough time for two possessions by the Sixers.

In that situation, the clock doesn’t start until a player on the court touches Bill Russell’s inbound pass.

With the Sixers playing tight defense, Bill Russell lobbed a pass high into the air. But – get this – the ball hit a wire that was hanging down from the rafters – a wire that helped support the basket.

Whistles sounded.

Dead ball.

Ball out Sixers – under their own basket – with those five seconds still showing on the clock.

Suddenly, the Sixers found themselves in position to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. A basket here and the Sixers would steal a win and advance to the NBA Finals.

Sixers coach Dolph Schayes called a play.

Hal Greer was going to initiate the inbound pass.

Would Greer bounce a pass to Wilt underneath for a dipper-dunk? Would he see a cutter going hell-bent toward the basket for a layup. Or would he find an open man for a buzzer-beater?

The Celtics set their defense.

Hal Greer slapped the ball to set the play in motion.

Greer’s first option was Wilt underneath, but Bill Russell was standing between Greer and Wilt – poised to intercept.

Greer was trying finding an open man, but no one was moving. Plus, K.C. Jones was waving his arms frantically in an attempt to obstruct Greer’s vision – and he was succeeding.

With the referee counting time, Greer finally spotted Chet Walker – who appeared to be wide open because John Havlicek seemed to be disinterested in playing defense. Havlicek wasn’t very close to Walker – plus his back was facing Greer. He wasn’t even watching. So Greer reared up on tip-toes – to get a better view – and then jumped and lofted a pass toward the open Chet Walker.

But John Havlicek had been playing possum. In fact, much like a ball-hawking NFL cornerback, he was baiting Greer into passing to Walker. And he was silently counting down the five seconds Greer was allocated to make the pass. At the count of four, Havlicek spun around and spotted the ball on its trajectory toward Chet Walker.

Thus came Celtics play-by-play announcer Johnny Most’s opportunity to make the call of a lifetime – a call that stands alongside two of the greatest calls in the history of sports.

• “The Giants win the pennant. The Giants win the pennant,” was how Russ Hodges called Bobby Thompson’s shot-heard-round-the-world to win the 1951 National League playoff game between the New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers.

• “Ladies and gentlemen, the Flyers are going to win the Stanley Cup. The Flyers win the Stanley Cup. The Flyers win the Stanley Cup. The Flyers have won the Stanley Cup,” was the way Gene Hart called the Philadelphia Flyers victory over the Boston Bruins to win the 1974 Stanley Cup.

The classic call by Johnny Most went like this:

“Greer is putting the ball in play. He gets it out deep, and Havlicek steals it. Over to Sam Jones. Havlicek stole the ball. It’s all over … It’s all over.

Johnny Havlicek is being mobbed by the fans. It’s all over. Johnny Havlicek stole the ball.

Oh my, what a play by Havlicek at the end of this ball game.”

Fifty years ago, I was watching that game on TV and those final five seconds were one tumultuous roller-coaster ride as my emotions swung the gamut from defeat – to exhilaration – to expectation – to down-and-out desolation.

This is not hindsight, but I never understood why Dolph Schayes had Hal Greer making the inbound pass. To this day, Hal Greer is one of the most under-rated guards in NBA history. He’s still the leading scorer in the combined Nationals-Sixers franchise history with 21,586 points. Allen Iverson is second with 19,931 points.

Hal Greer had ice water in his veins and he was money at crunch time. I would’ve had Hal Greer as the target of the inbound pass. But that wasn’t the way Dolph Schayes saw it.

So when Havlicek stole ball, my heart sunk. The Sixers had it for the taking – but let it slip away.

The Celtics went on to win another NBA championship by beating the Los Angeles Lakers four games to one.

But the Sixers would regroup. Two years later, they won it all with what was arguably the greatest basketball in NBA history.

Barry Bowe is the author of Born to Be Wild, 1964 – The Year the Phillies Blew the Pennant, and 12 Best Eagles QBs.

Comments

No Comments