On March 29, 1984, like a thief in the night, Baltimore Colts owner Robert Irsay placed an order for fifteen Mayflower moving vans to report to the Colts facilities in Owings Mills, Maryland. The vans arrived at 2:00 AM.

To begin with, Irsay was dissatisfied with the team’s current digs in antiquated Memorial Stadium. Plus, he was frustrated by a municipal government that refused to upgrade the stadium. And, finally, he was so incensed when the city informed him that his rental fees were being raised, that he threatened to move the Colts out of Baltimore.

That day, he was making good on his threat.

Earlier that day, the mayor of Indianapolis offered Irsay a $12,500,000 loan, a $4,000,000 training complex, and the use of the brand new Hoosier Dome if Irsay moved the Colts from Baltimore to Indy.

Fearing that the Maryland House of Delegates would approve the eminent domain bill the next morning and seize the Colts just as soon as the governor signed the bill into law, Irsay moved fast.

Workers loaded the Colts’ belongings and, one by one, the trucks pulled out of Owings Mills. By 10 a.m. the entire fleet was on the road. By then, however, the governor had signed the bill into law and dispatched state police cars toward Owings Mills to block any movements by the Colts.

But not only were the troopers too late, but they were also outflanked.

To avoid detection, all fifteen Mayflower vans were taking different routes out of state – passing through Pennsylvania, Virginia, and/or West Virginia on the way to Ohio and Indiana. One by one, all fifteen vans made it to the Indiana border. As each van arrived, Indiana state troopers were waiting to escort it the rest of the way to Indianapolis.

At that time, I was working in Center City Philadelphia, but working for a company headquartered in Towson, Maryland. Many of my close business associates lived in Baltimore and had been staunch Colts fans all of their lives. That day, I spent time on the phone with all of them. They were devastated.

If you’re not, say, forty or so, you may have no idea how close we Eagles fans came to experiencing the same sort of treachery. In December of that same year, 1984, Eagles owner Leonard Tose had already shaken hands with Phoenix real-estate developer James Monaghan to sell 25% of the Eagles for $40-milllon – and, get this, to move the Eagles to Phoenix. The deal was going to be announced on December 17 – the day after the Eagles ended the season by playing the Falcons in Atlanta.

Bob Hurt, a columnist for the Arizona Republic, was to fly first-class to Atlanta to meet up with Monaghan, Tose, and Tose’s daughter Susan Fletcher, who by then was the Eagles chief legal counsel. From there, the four of them would fly to Phoenix to announce the sale of the Eagles.

What saved our hash as Eagles fans was that, six days prior to December 17, Bob Hurt wrote about what was supposed to happen six days hence.

That story exploded in Philadelphia and created widespread furor among fans, media members, and politicians. Tose immediately denied the story.

“The Eagles aren’t going anywhere,” Tose told the press. “In the first place, I’m not going to sell the club. In the second place, even if I ever did, the only way they’d get them out of Philadelphia is over my dead body.”

Jim Murray was the Eagles GM under Tose until replaced by Tose’s daughter in 1983.

“His plan was as real as rain,” Murray said about the planned sale of the Eagles and the move to Phoenix.

Tose’s daughter Susan Fletcher had already made several trips to Phoenix, working out arrangements of the sale, and enrolling her children in a private school.

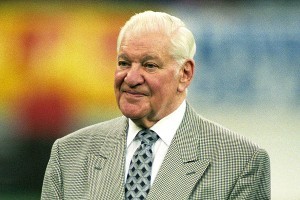

It was a shame. Leonard Tose was a self-made millionaire in the trucking industry. He’d been involved with ownership of the Eagles for decades. He was part of “The Hundred Brothers” who bought the Eagles from millionaire playboy Lex Thompson in 1949 and owned the team until they sold out to Jerry Wolman in 1963. And he was Johnny-on-the-spot to pony up $16.1-million when Jerry Wolman was forced to sell the Eagles in 1969 due to financial distress.

Always an Eagles fan, Tose was a good owner. He hired Dick Vermeil, who transformed the Eagles from NFL doormats to Super Bowl participants. He loved his team.

Unfortunately, he loved cigarettes, alcohol, and women – he was married five times. But he loved to gamble most of all.

His losses in the Atlantic City casinos are legendary – losses that led to financial distress of his own. By 1984, his debt was estimated to be somewhere between $30-42-million.

The City of Philadelphia tried to help Tose by making concessions:

– Construction of more the 50 penthouse suites – all revenues going to the Eagles.

– Reworking of a more-favorable lease arrangement

– Deferring collection of rental fees of $800,000 per season for ten years

– Construction of two practice fields and an indoor training facility

And the NFL tried to bail him out by securing a loan enabling him to restructure his debt.

But neither the City of Philadelphia nor the NFL could save Leonard Tose from his addictions.

The sale to Monaghan and the move to Phoenix never happened. But by 1985, the meter had run out on Tose and he had no choice but to sell the Eagles for $65-million to Norman Braman.

In 2003, Leonard Tose died a broken man – and a broke man. He was 88.

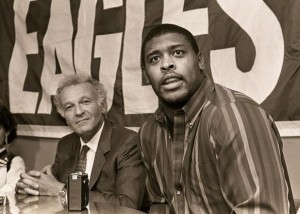

(The photo in the header shows Leonard Tose welcoming 1983 first-round draft choice Kenny Jackson, out of Penn State, with his daughter and Eagles general counsel Susan Fletcher looking on.)

(Some of the material used in this story was gleaned from two philly.com articles from 2009 – one written by Paul Domowitch and the other by Frank Fitzpatrick – and the Wikipedia entry about the Baltimore Colts relocation to Indianapolis.)

Barry Bowe is the author of 12 Best Eagles QBs and 1964 – The Year the Phillies Blew the Pennant.

Comments

No Comments