On February 11, 1968, black Memphis sanitation workers staged a walkout to protest unequal wages and working conditions.

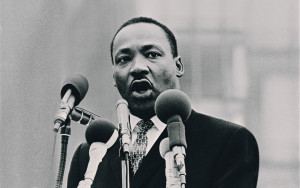

On April 3, or some seven weeks later, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. traveled to Memphis to make a speech in support of the black sanitation workers. His arrival in Memphis had been delayed somewhat to validate bomb threats against the plane that was scheduled to transport him to Memphis.

On April 3, or some seven weeks later, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. traveled to Memphis to make a speech in support of the black sanitation workers. His arrival in Memphis had been delayed somewhat to validate bomb threats against the plane that was scheduled to transport him to Memphis.

Such threats had become part and parcel of his life by then.

When Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated John F. Kennedy five years earlier, King told his wife Coretta, “This is what is going to happen to me also. I keep telling you, this is a sick society.”

King was right on both counts. For starters, America was going to hell in the proverbial hand basket as the decade of the 1960s progressed.

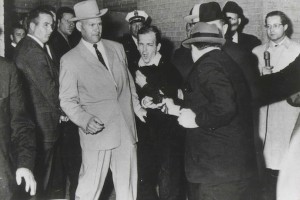

Just two days after JFK was assassinated, Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald in a Dallas police station – live on national TV.

Just two days after JFK was assassinated, Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald in a Dallas police station – live on national TV.

With Kennedy dead, Lyndon Johnson inherited the Oval Office, created the Warren Commission, and the Conspiracy Theory was hatched. Arlen Specter formulated his magic-bullet theory, the Zapruder film made you scratch your head, and the Grassy Knoll became legendary.

The Beatles invaded the U.S. and in the words of John Lennon “became more popular than Jesus.” Through their lyrics, Lennon and Paul McCartney shared their newly gained philosophies about mind expansion with their worshiping masses. Not coincidentally, drug abuse soared throughout the country.

Spurred on by Martin Luther King, integrationists marched throughout the South, sat-in at lunch counters, and went to the bathroom in rest rooms marked WHITE ONLY. Rosa Parks resisted segregation by riding in a front seat of a bus. Afros sprouted, riots flared, and inner cities burned from Los Angeles, to Chicago, to Detroit, to Philadelphia, to Newark, New Jersey.

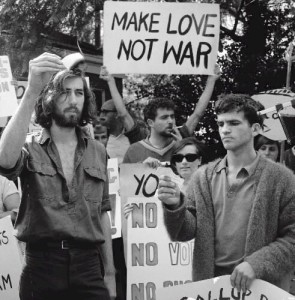

Flower children bloomed, hippies flashed peace signs and donned love beads, and teenagers were running away from home in droves to join communes. A generation of teenagers started smoking pot, copping ludes, popping speed, dropping acid, shooting dope, huffing glue, and doing their own thing with banana peels and mushrooms.

Peaceniks burned draft cards and draft dodgers crossed the Canadian border to avoid the military. Halfway around the world, medics kept shipping home brave American patriots in body bags.

Peaceniks burned draft cards and draft dodgers crossed the Canadian border to avoid the military. Halfway around the world, medics kept shipping home brave American patriots in body bags.

On Broadway, actors and actresses stripped off their costumes and paraded around the stage totally nude in the production of Hair.

At public demonstrations, liberated women burned their bras and from those lace and whalebone ashes sprung the sexual revolution. By coupling those liberated women with the development of birth-control pills, there came a wild spree of free sex, daisy chains, wife-swapping, and sport-fucking.

Into this arena, some of our fighting men started returning home from Vietnam, many of them bringing back exotic Southeast-Asian strains of gonorrhea. Despite 5,000,000-millimeter doses of penicillin, penises kept dripping, and a VD epidemic spread among the heterosexual population. While at the same time, gays were coming out of closets from Greenwich Village to San Francisco, and syphilis was running rampant in the homosexual communities.

Monogamous relationships bottomed out, divorce skyrocketed, and religion lost its appeal.

The Leave It to Beaver American family of the 1950s disintegrated.

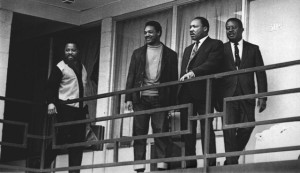

Early on the evening of April 4, 1969 – exactly 46 years ago today – Martin Luther King, Jr, was standing on an exterior second-floor balcony outside the Lorraine Motel in Memphis.

Early on the evening of April 4, 1969 – exactly 46 years ago today – Martin Luther King, Jr, was standing on an exterior second-floor balcony outside the Lorraine Motel in Memphis.

At 6:01 p.m., a Remington Model 760 rifle discharged a single .30-06 bullet. The bullet struck Dr. King’s right cheek and broke his jaw upon entry. The projectile then traveled a short distance down his spinal cord, breaking several vertebrae and severing his jugular vein in the process – before lodging itself in his right shoulder.

The force from the bullet knocked Dr. King onto the floor of the balcony.

The bullet had been shot from a boarding house across the street and a white man was seen fleeing soon after the shot was fired.

Dr. King was rushed to the hospital. Unsuccessful efforts were made to revive him and he was pronounced dead at 7:05 p.m.

The news was shocking – yet at the same time not surprising.

Just as Dr. King had premonitions about being murdered in cold blood, members of both the black and the white communities could perceive something like that happening as well. Nothing was surprising in the prevailing social climate of the late 1960s.

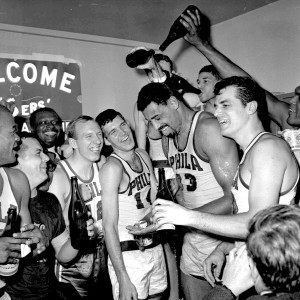

One year earlier, the Philadelphia 76ers won the NBA championship with what was arguably the greatest basketball team ever assembled. Wilt Chamberlain, Hal Greer, Chet Walker, Luke Jackson, Wali Jones, and Billy Cunningham were the stars.

One year earlier, the Philadelphia 76ers won the NBA championship with what was arguably the greatest basketball team ever assembled. Wilt Chamberlain, Hal Greer, Chet Walker, Luke Jackson, Wali Jones, and Billy Cunningham were the stars.

This year’s team was pretty much the same team – except for the addition of a jumping jack named Johnny Green, who provided a tremendous injection of energy coming off the bench.

That season was historic in regard to both the Flyers and the Sixers. It was the year when the brand new Spectrum opened in South Philadelphia – and the year when the roof blew off the Spectrum in February prior to a scheduled matinee of the Ice Capades.

While the roof was being repaired, the Flyers moved their home games to Quebec City and the Sixers played hopscotch between Convention Hall and the Palestra.

At almost the same time that Martin Luther King was being pronounced dead in the E.R. at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Memphis, the puck was being dropped to reopen the Spectrum. The Flyers were playing the St. Louis Blues in the first game of the Eastern Quarterfinals. The Flyers lost the game 1-0 and went on the lose the series 4-3.

At that time, I was working in sales in Philly and had some flexibility in my schedule.

Somewhere around mid-morning on April 5, the day after the assassination, I got a call from the Hellertown Welder – aka Glenn Roy Brown. Did I have time to pick up tickets for the Sixers game that night?

The Sixers were scheduled to open the Eastern Division Finals against the arch-rival Boston Celtics. The Sixers had advanced to the Eastern Finals by disposing of the New York Knicks four games to three. We were thinking and hoping that the Sixers were going to repeat as NBA champs.

But because of the assassination, the game was in limbo.

News of the assassination prompted major outbreaks of racial violence in cities across the country – which caused more than 40 deaths and extensive property damage. Sixers officials feared similar protests outside the Spectrum.

In fact, there were two games slated for that night and both were in jeopardy of postponement. Out West, the San Francisco Warriors were scheduled to play the Lakers in L.A. in the first game of the Western Division playoffs. Players from all four teams were going to vote on whether or not they would play the game – or postpone it.

Taking no chances, I drove to the Spectrum and bought four tickets – pretty sure they cost around eight bucks a piece. Even if the game were canceled, the tickets would be good when the game was eventually played, so we had nothing to lose.

For us, the good news was that the players voted to play. There was a strong police presence surrounding the Spectrum – but the safety precautions proved unnecessary. There was no violence.

So I went to the game with the Welder and Donnie Mears and my dad Ed Bowe. The Welder and Donnie and I were good pals and played a lot of basketball together over the years. The Welder could shoot the lights out from pretty much anywhere in the half-court.

So I went to the game with the Welder and Donnie Mears and my dad Ed Bowe. The Welder and Donnie and I were good pals and played a lot of basketball together over the years. The Welder could shoot the lights out from pretty much anywhere in the half-court.

My dad’s the one responsible for this site being called Blame My Father.

There was a moment of silence for Martin Luther King prior to the opening tap, and then the game proceeded as if nothing happened.

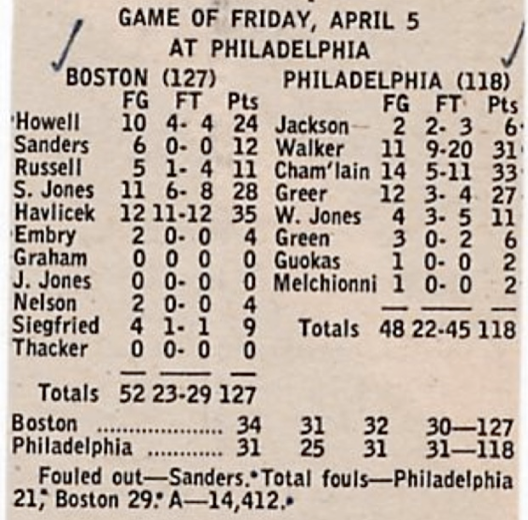

The game was a good one, but the Sixers came up short by a 127-118 score. They would rebound to take a 3-to-1 lead in the series – but then lost three straight and hopes of a repeat championship went down the drain.

My Six Degrees of Separation from James Earl Ray

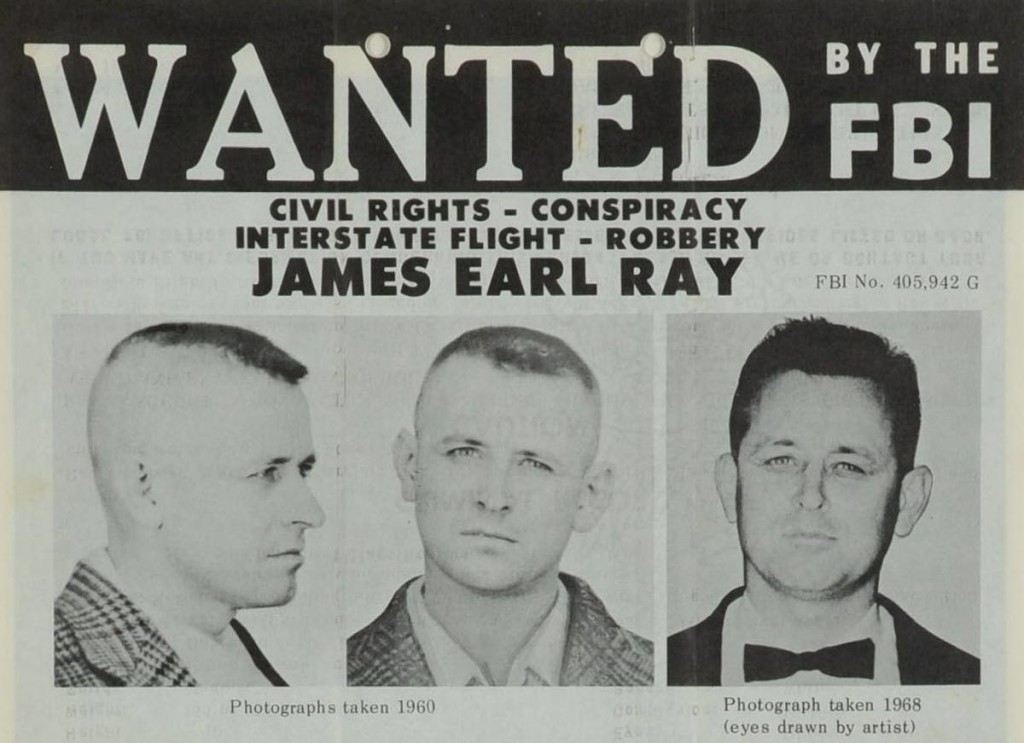

Witnesses identified 40-year-old James Earl Ray as Martin Luther King’s shooter – but two months passed without a sighting of the suspect.

On June 8, Scotland Yard officers arrested Ray as he disembarked at London Airport as he was changing planes en route from Lisbon, Portugal to Brussels, Belgium.

James Earl Ray hired Percy Foreman to defend him. Foreman was a high-powered criminal defense attorney from Houston. Ray pleaded guilty on March 10, 1969. By pleading guilty, he escaped the death penalty but was sentenced to 99 years in prison.

Dick DeGuerin was Percy Foreman’s protégé, and Percy was a good teacher. So good, that in 1994, Dick was named the Outstanding Criminal Defense Lawyer of the Year in Texas. Some of Dick’s better-known clients were New York Mets ballplayers Lenny Dykstra and Keith Hernandez, former Texas governor Kay Bailey Hutchinson, and Waco cult leader David Koresh.

In that same year of 1994, Dale Brown became the lone defendant in the infamous Operation Lightning Strike trial which pitted him against the FBI in federal court in Houston. Dale was an aerospace engineer at the Johnson Space Center and Dale hired Dick DeGuerin to defend him.

Hoping to transform his predicament into a book and/or a movie deal, Dale contacted my literary agent at the time Peter Miller and Peter referred Dale to me.

Dale retained me to produce book and movie proposals.

Operation Lightning Strike was perhaps the most-spectacular legal incident involving the Houston space center. For six months, I worked on Dale’s defense team with Dick DeGuerin. Out of fear of retaliation from rogue FBI agents, Dale and I took refuge in a safe-house outside of Houston for two months.

Dale – a young and healthy male of 32 – almost died under mysterious, germ-warfare-like conditions – twice. He wound up paralyzed.

At the conclusion of the court proceedings, I changed planes in Dallas on my way back home to Philly. I can remember ducking behind columns at the Dallas airport to make sure I wasn’t being followed. Such was our paranoia. Fortunately, I wasn’t being followed.

Unfortunately, because Dale’s first trial ended with a hung jury, we found no buyers for a book or a movie about Operation Lightning Strike.

It was an exciting albeit scary experience – and those are my six degrees of separation from assassin James Earl Ray.

I was never a fan of Martin Luther King’s activities – nor was I a detractor. As a young white male living in a white middle-class environment, I couldn’t relate to the black man’s crusade for equality. I took it for granted. But I certainly respected the man’s dedication and courage.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was one of the bravest men in the history of America.

Barry Bowe is the author of Born to Be Wild, 1964 – The Year the Phillies Blew the Pennant, and 12 Best Eagles QBs.

Comments

No Comments