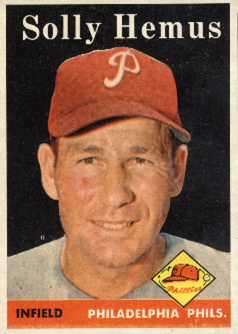

Solly Hemus was a hot-head and a racist.

Solly Hemus was a hot-head and a racist.

His baseball career was delayed because he enlisted in the Navy right out of high school and served on active duty for four years during World War II. After being discharged in 1946, he picked up his glove and spikes and gave baseball his best shot.

But he was a Punch-and-Judy middle infielder who often let his temper get the better of him. In his own words:

“I was originally signed by the Dodgers. They released me in spring training after I got into an argument with the manager going to Fort Worth. It was my fault because I shouldn’t have been popping off at the mouth. But I was a young guy and I didn’t know nothing anyway.”

Hemus spent seven years in the minor leagues – four years with the Pocatello Cardinals of the Class C Pioneer League and another three seasons with the Class AA Houston Buffaloes of the Texas League. He finally broke into the big leagues with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1949. He was a 26-year-old rookie by then.

He made himself into a good hitter by being selective – batting .273 over 11 National League seasons – eight years with the Cards, two years with the Phillies, and one year split between St. Louis and Philadelphia. He set a National League record by walking five times in a game during the 1950 season and in 1953 he led the league in getting hit by pitches with 12. In 1954 – his best season – he batted .304 with a .453 OBP.

Over the years, Solly Hemus learned the intricacies of the game of baseball. So much so that, at the beginning of the 1959 season, the Cardinals named him as the player/manager.

While managing the Cardinals, Hemus tried to convince Bob Gibson and Curt Flood that they weren’t good enough to make it in the majors. He tried to persuade them to try another line of work. His motivation to do so – according to both Gibson and Flood – was racial.

In his autobiography Stranger to the Game, Bob Gibson describes his “struggles with racist manager Solly Hemus.” Curt Flood describes his problems with Hemus in pretty much the same terms in his autobiography The Curt Flood Story.

Ergo, it was delicious irony that Solly Hemus would become a pawn when the Phillies finally broke the color barrier in 1957.

The date was April 22, 1957 – exactly 58 years ago today.

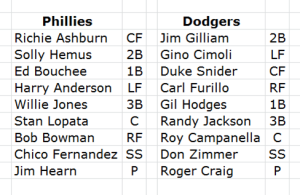

The Phillies were playing the Brooklyn Dodgers.

By an amazing coincidence, yesterday I wrote “Jersey City Dodgers” about when the Phillies played the Brooklyn Dodgers at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City in 1956. This historic game was also played at Roosevelt Stadium – but one year later.

By an amazing coincidence, yesterday I wrote “Jersey City Dodgers” about when the Phillies played the Brooklyn Dodgers at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City in 1956. This historic game was also played at Roosevelt Stadium – but one year later.

It was Jim Hearn for the Phillies versus Roger Craig for the Dodgers.

Solly Hemus was starting at second for the Phillies.

The Phillies were trailing 3-1 as the game entered the top of the eighth.

Frankie Baumholtz led off for the Phillies by grounding a ball to Gil Hodges at first, and Hodges easily beat Baumholtz to the bag for the first out.

Richie Ashburn lined a 1-2 pitch into center – bringing Hemus to the plate. Batting .333, Hemus lined a double to right – but Ashburn had to hold at third.

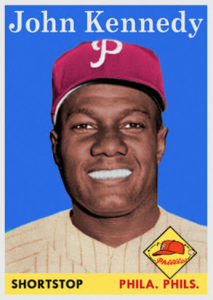

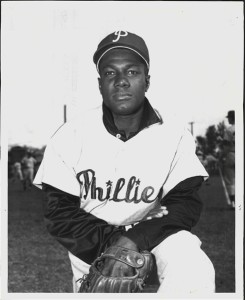

Dodgers manager Walter Alston felt that Craig had run out of gas. So he made the call to the bullpen for Clem Labine. And while Labine was making his warm-up tosses, Phillies manager Mayo Smith made Phillies history by sending reserve shortstop John Kennedy into the game as a pinch-runner for Solly Hemus.

Dodgers manager Walter Alston felt that Craig had run out of gas. So he made the call to the bullpen for Clem Labine. And while Labine was making his warm-up tosses, Phillies manager Mayo Smith made Phillies history by sending reserve shortstop John Kennedy into the game as a pinch-runner for Solly Hemus.

That move made John Kennedy the first black ballplayer to play for the Phillies. The Phillies had purchased Kennedy’s contract from the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues – where Kennedy was competing for the batting title.

Clem Labine retired Eddie Bouchee and Harry Anderson – stranding both Ashburn and Kennedy.

Mayo Smith replaced Kennedy in the bottom half of the inning with Phillies reliever Turk Farrell. So Kennedy racked up no stats for his first appearance – other than a “1” in the “G” column.

John Kennedy got into only five games that rookie season. He went to bat twice without getting a hit. Used as a pinch-runner twice, he scored one run. He made two appearances in the field at shortstop – getting one assist, committing one error, and participating in one double play.

John Kennedy got into only five games that rookie season. He went to bat twice without getting a hit. Used as a pinch-runner twice, he scored one run. He made two appearances in the field at shortstop – getting one assist, committing one error, and participating in one double play.

Kennedy was sent back to the minors before the month ended and toiled in the Phillies chain for the next four seasons:

• One season with the High-Point-Thomasville (North Carolina) Hi-Toms of the Class B Carolina League – batting .270 in 120 games.

• One season with the Tulsa Oilers of the Class AA Texas League – batting .225 in 119 games.

• One season with the Des Moines Demons of the Class B Three-I League (Illinois, Indiana, and Iowa) – bating .228 in 88 games.

• And one season with the Class A Asheville (North Carolina) Tourists of the SALLY (South Atlantic) League – batting .246 in 104 games.

Seeing limited potential, the Phillies released John Kennedy after the 1960 season.

In 1961, he played one game with the Jacksonville Jets of the SALLY League – going 1-for-4 – before calling it quits at the age of 34.

While his major league career consisted of the proverbial cup of coffee, John Kennedy made Jackie-Robinson-style history for the Phillies.

John Kennedy died in 1998 at the age of 71 in Jacksonville.

Solly Hemus, on the other hand, managed the Cardinals for three seasons. After that, he served as a coach with the New York Mets in 1962 and 1963 and with the Cleveland Indians in 1964 and 1965. He managed the Mets AAA Jacksonville Suns in 1966 before leaving baseball to enter the oil industry in Houston.

As of this writing, he’s still alive at 92.

Barry Bowe is the author of Born to Be Wild, 1964 – The Year the Phillies Blew the Pennant, and 12 Best Eagles QBs.

Comments

No Comments