I have a relatively new Twitter buddy who goes by the handle George K – but I’ve been listening to him for years as a regular caller on WIP. He used to call himself Baseball George, but he recently modified his moniker to Baseball Giorgio. You’ll especially hear him when Rickie Ricardo or Jody McDonald are on the air.

Rickie and Jody are baseball guys – and Baseball Giorgio is a baseball guy.

The other day, Baseball Giorgio retweeted a photo posted by the Wrigley Field Blog.

The year 1938 struck a nerve.

Some of my earliest baseball memories involve the 1950 Whiz Kids when the Phillies played the Yankees in the World Series. I was in second grade and Mrs. Bender was a baseball fan. She let us listen to the World Series games on the radio during classes – they played day games in the Series back then.

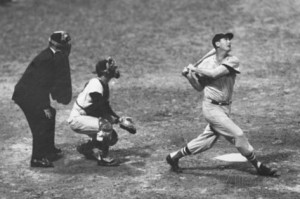

Joe DiMaggio – the Yankee Clipper – put fear into the hearts of young Phillies fans such as myself.

Joe DiMaggio – the Yankee Clipper – put fear into the hearts of young Phillies fans such as myself.

In Game 1 – Vic Raschi bested Jim Konstanty 1-0. And in Game 2 – true to form – Joe DiMaggio hit a home run in the top of the tenth to beat the Phillies 2-1. DiMaggio hit the homer off Phillies ace Robin Roberts and the loss plunged the Whiz Kids into a hole they couldn’t climb out of.

Getting back to 1938 striking a nerve, you don’t have to be a math major to figure out that the 1950 World Series came twelve years after the 1938 World Series. It never dawned on me that Joe DiMaggio could have been playing two decades prior to the 1950s. So I had to look him up.

While looking at the Yankee Clipper’s stats at baseball-reference.com, an idea struck me as soon as I noticed that he missed three full seasons due to the following – “Did not play in major or minor leagues (Military Service).” If you’re not from my generation, you probably have no idea how many ballplayers from the past had their careers interrupted to serve our country. So here’s a little history and background.

Modern military conscription – usually referred to as the draft – began in the United States during World War I on June 15, 1917, and ended on June 1, 1973. For any non-math majors out there, that’s two weeks short of lasting for 56 years. During that period, men between the ages of 18 and 25 were required to register with the Selective Service System so they could be drafted into the military if and when needed.

When Germany invaded and conquered France during the summer of 1940, more than two-thirds of U.S. residents believed that continued invasions by German forces would endanger the United States.

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1942, the threat of foreign invasion became real and the age limit for eligible draftees was expanded to include men between the ages of 18 and 64.

Professional athletes were not exempt from the draft. Therefore, many athletes in all sports had their careers interrupted by military duty. The most graphic example is Ted Williams – but I’ll get to him soon enough – and I’ll also get to Curt Simmons. But for now, let’s get back to Joltin’ Joe.

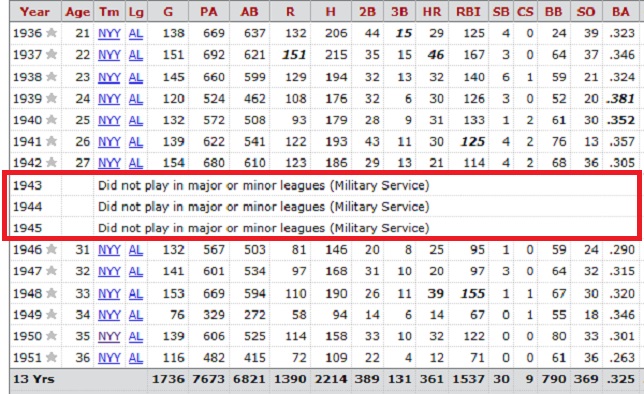

Thanks to baseball-reference.com, here’s Joe DiMaggio’s lifetime stats.

Joe DiMaggio didn’t play in 1943, 1944, and 1945 and those are three of the prime years in a baseball player’s career – ages 28, 29, and 30. He was serving military duty in the Army.

DiMaggio played for 13 years and hit 389 HRs. Doing some simple math, that’s an average of 28 HRs per season. Hypothetically, if DiMaggio didn’t miss those three seasons, he would’ve hit 473 HRs – and you can do the same thing with the rest of his stats.

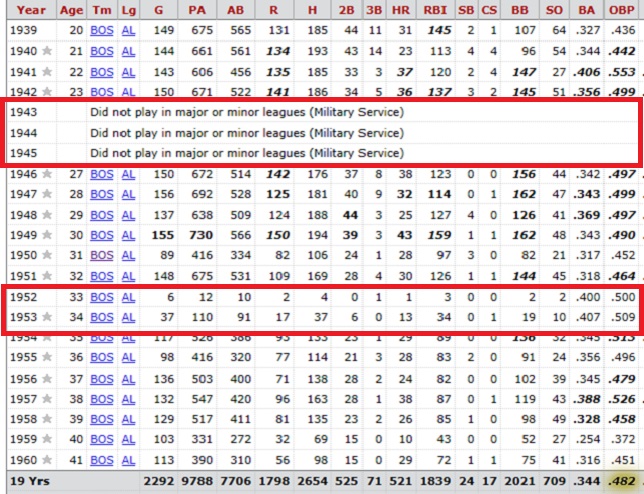

Now let’s take a look at Ted William’s lifetime stats.

Ted Williams was the greatest hitter I ever saw – lifetime average of .344 and an OBP of .482 while hitting 521 HRs and collecting 1,839 RBIs. He hit .406 in 1941 – and we’ll never see another .400 hitter. But look at the two red boxes above.

Ted Williams was the greatest hitter I ever saw – lifetime average of .344 and an OBP of .482 while hitting 521 HRs and collecting 1,839 RBIs. He hit .406 in 1941 – and we’ll never see another .400 hitter. But look at the two red boxes above.

Ted Williams enlisted in the Navy Reserve at the outbreak of World War II in 1942 and went on active duty early in 1943. He opted out of the Navy and into the Marine Corps, and was commissioned a second lieutenant on May 2, 1944. He played on the Chapel Hill, North Carolina, baseball team during pre-flight training.

After earning his wings, he was stationed overseas as a fighter pilot and served in that capacity until the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 18, 1945. Williams was then sent to Pearl Harbor. There, he played baseball in an eight-team Army League along with Joe DiMaggio and Stan Musial. That year, the Army-Navy championship game on Pearl Harbor drew 40,000 fans.

Williams was discharged on January 28, 1946, but he’d lost three years of his baseball career by then – 1943, 1944, and 1945. But that wasn’t the extent of his military service.

He played for the Red Sox for the next eight years. Then, on May 1, 1952, his baseball career was once again put on hold.

At the age of 33, the Marine Corps recalled Ted Williams to active duty to serve in the Korean War. He turned down a soft assignment of playing for a service baseball team to take a refresher flight-training course. He soon qualified to fly the F9F Panther jet and was sent to the Marine Aircraft Group 33 in Pohang, South Korea. There, he flew 39 combat missions and was John Glenn’s wingman on more than half of those missions.

John Glenn called Ted Williams one of the best pilots he ever saw.

Williams was hospitalized with pneumonia in June 1953 and was left with an inner-ear infection that disqualified him as a pilot. He was soon discharged.

The second red box doesn’t contain the message that Williams didn’t play during 1952 and 1953 because he played in 6 games at the beginning of 1952, before he left for Korea, and he played in 37 games at the end of 1953, after being discharged. This time, he’d lost more than a year of baseball while serving in Korea. In all, Ted Williams lost nearly five years of his baseball career while serving his country.

Just imagine what his career numbers might’ve looked like.

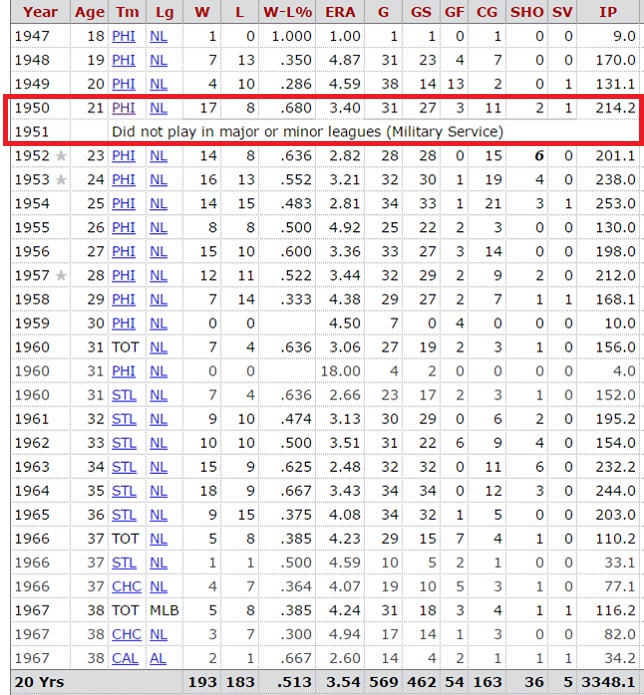

And last but not least comes Phillies left-hander Curt Simmons.

The surprise team of the 1950 season was the Whiz Kids.

On September 2, 1950, Curt Simmons pitched a 7-hit, 2-0 shutout against Johnny Sain and the Boston Braves to up his record to 17-8 and put the Whiz Kids a full seven games ahead of the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Phils looked like a shoe-in to easily take the pennant. But Curt Simmons had already been served with his draft papers.

On September 2, 1950, Curt Simmons pitched a 7-hit, 2-0 shutout against Johnny Sain and the Boston Braves to up his record to 17-8 and put the Whiz Kids a full seven games ahead of the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Phils looked like a shoe-in to easily take the pennant. But Curt Simmons had already been served with his draft papers.

He got two more starts before his call to duty – both no-decisions. But after Simmons left the team on September 9, the Whiz Kids started to falter. When the last day of the season arrived, the Phils needed a win over the second-place Dodgers, in Brooklyn, to avoid being tied by the Dodgers for first place.

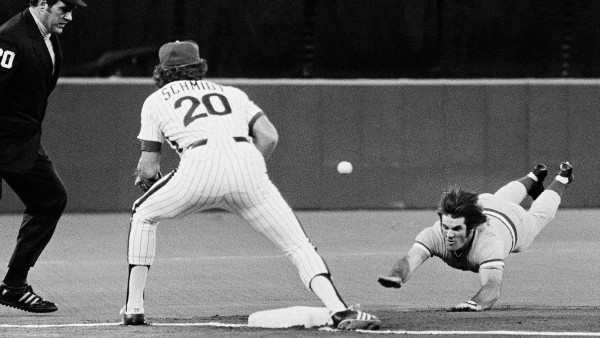

It took a game-saving throw from Richie Ashburn in the bottom of the ninth that nailed Cal Abrams at home plate to save the game – and a three-run homer by Dick Sisler in the top of the tenth to survive.

The Phillies advanced to a World Series appearance against the Bronx Bombers.

The Phillies were swept by the Yankees in the Series – but three of the losses were very close games. Had not Curt Simmons been lost to the Army, I believe that (1) Curt Simmons would’ve been a 20-game winner, (2) the Phillies would’ve easily won the NL pennant, and (3) the Phillies would’ve been a legitimate threat to upset the Yankees.

Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, and Curt Simmons are but three examples of how the military draft changed sports history. So if you ever go back to try to compare the careers of the baseball stars of the 1940s and 1950s with players from later decades, you can’t. So many of them sacrificed big personal numbers while serving their country in the primes of their careers.

Thanks to Baseball Giorgio for the idea.

Barry Bowe is the author of 1964 – The Year the Phillies Blew the Pennant and Born to Be Wild.

Comments

No Comments